Cydonia Mensae

The part of Mars that

has attracted most attention since satellite exploration of the planet began is

the Cydonia Mensae region, located in the planet’s northern hemisphere. The

region bears traces of former shorelines—it is now accepted by most

astronomers that Mars was once home to large bodies of water—and of eroded

hills and mountains, corresponding to terrestrial buttes and mesas. A number of

features were seen on Viking Orbiter photographs from the mid 1970s that led

some researchers to suggest that they were artificial in origin. One of the most

impressive parts of this claim was the concentration of anomalies in a single

area; these anomalies included what was claimed to be an enormous carved face,

three- and five-sided pyramids showing bilateral symmetry and walled compounds.

Moreover, some of these features appeared to be in alignment with each other.

The so-called ‘face’ has attracted most attention.

The ‘face’

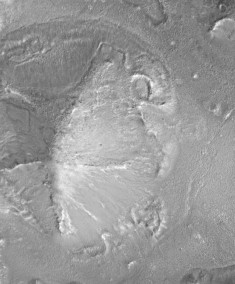

The ‘face’ has

been known as that since NASA engineers dubbed it such as a convenient shorthand

[i].

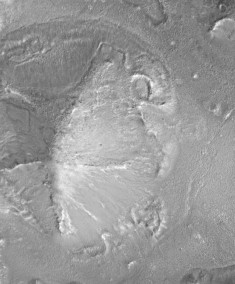

Located at about 40.9ºN 9.45ºW, it was photographed by the Viking Orbiters 1

on 25 July 1976 whilst obtaining images of a site suitable for Viking Lander 2.

Eighteen images of the region were taken, but of these, eleven have resolutions

worse than 550 m per pixel (in other words, no feature less than 550 m across

can be seen on these images). Only two of them (frames 070A13, taken on 24

August 1976, and 035A72, taken on 20 July 1976) have resolutions of better than

50 m per pixel. They show a subrectangular elevated feature that displays

roughly bilateral symmetry similar to a human face. The length is estimated as 2

km, the width as 1.5 km and the height as about 400 m. The long axis of the face

is aligned at a bearing of approximately 329º to the Martian North Pole. In

Image 070A13, the sun is 28º above the horizon, while in 035A72, it is 11º;

these differences in angle reveal slightly different details in the ‘face’.

The ‘face’ has

been known as that since NASA engineers dubbed it such as a convenient shorthand

[i].

Located at about 40.9ºN 9.45ºW, it was photographed by the Viking Orbiters 1

on 25 July 1976 whilst obtaining images of a site suitable for Viking Lander 2.

Eighteen images of the region were taken, but of these, eleven have resolutions

worse than 550 m per pixel (in other words, no feature less than 550 m across

can be seen on these images). Only two of them (frames 070A13, taken on 24

August 1976, and 035A72, taken on 20 July 1976) have resolutions of better than

50 m per pixel. They show a subrectangular elevated feature that displays

roughly bilateral symmetry similar to a human face. The length is estimated as 2

km, the width as 1.5 km and the height as about 400 m. The long axis of the face

is aligned at a bearing of approximately 329º to the Martian North Pole. In

Image 070A13, the sun is 28º above the horizon, while in 035A72, it is 11º;

these differences in angle reveal slightly different details in the ‘face’.

The ‘face’ lies

close to the boundary between an area of flat-topped mesas and conical hills to

its southwest, and a much flatter region in which it lies. Claims have been made

for the presence of a former shoreline close to the ‘face’, which may be

important in considering its likely origin. Erosion is generally cited as the

main factor in the creation of the landforms in this region, but a variety of

claims were made during the 1980s and 90s that this was not sufficient to

explain a number of features of the ‘face’. The original view of astronomers

was that the northern past of Mars had originally been covered with a sediment

that subsequently eroded, perhaps as a result of wind action. As evidence for

the former presence of surface water on the planet has increased, so it has

begun to seem more likely that the erosion in this region may have been

exacerbated by former seas.

The ‘face’ lies

close to the boundary between an area of flat-topped mesas and conical hills to

its southwest, and a much flatter region in which it lies. Claims have been made

for the presence of a former shoreline close to the ‘face’, which may be

important in considering its likely origin. Erosion is generally cited as the

main factor in the creation of the landforms in this region, but a variety of

claims were made during the 1980s and 90s that this was not sufficient to

explain a number of features of the ‘face’. The original view of astronomers

was that the northern past of Mars had originally been covered with a sediment

that subsequently eroded, perhaps as a result of wind action. As evidence for

the former presence of surface water on the planet has increased, so it has

begun to seem more likely that the erosion in this region may have been

exacerbated by former seas.

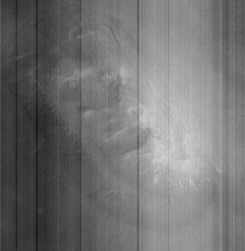

The initial announcement of the discovery of this feature dismissed it as being

‘formed by shadows giving the illusion of eyes, nose and mouth’. The public

took little notice of it until DiPietro and Molenaar published an analysis of

the formation in 1982, in which they concluded that it was artificial. Since

then, a number of popular writers have taken up the theme, most notably Richard

Hoagland and Graham Hancock. The widespread availability of computers for

processing digital images from the mid-1980s onwards led to a great deal of

amateur work on the Viking Orbiter photographs. Different techniques for

enhancing the photographs have been used, including techniques that attempt to

deduce three-dimensional shape from shadows, the interpolation of pixels and so

on. These techniques were all used to make the ‘face’ appear more detailed

and more humanoid than on the original satellite images. The ‘face’ has

become an iconic image, familiar to millions; its ghost-like features stare

blankly from the covers of numerous books and videos. Demands for photographs of

higher quality than those of 1976—with their resolutions of no better than 43

m per pixel—grew during the 1990s, especially when NASA announced the

forthcoming launch of Mars Observer on 22 September 1992. Equipped with a camera

that could achieve a best resolution of up to 1.4 m per pixel, the probe was

lost on 21 August 1993, three days before entering Martian orbit.

The initial announcement of the discovery of this feature dismissed it as being

‘formed by shadows giving the illusion of eyes, nose and mouth’. The public

took little notice of it until DiPietro and Molenaar published an analysis of

the formation in 1982, in which they concluded that it was artificial. Since

then, a number of popular writers have taken up the theme, most notably Richard

Hoagland and Graham Hancock. The widespread availability of computers for

processing digital images from the mid-1980s onwards led to a great deal of

amateur work on the Viking Orbiter photographs. Different techniques for

enhancing the photographs have been used, including techniques that attempt to

deduce three-dimensional shape from shadows, the interpolation of pixels and so

on. These techniques were all used to make the ‘face’ appear more detailed

and more humanoid than on the original satellite images. The ‘face’ has

become an iconic image, familiar to millions; its ghost-like features stare

blankly from the covers of numerous books and videos. Demands for photographs of

higher quality than those of 1976—with their resolutions of no better than 43

m per pixel—grew during the 1990s, especially when NASA announced the

forthcoming launch of Mars Observer on 22 September 1992. Equipped with a camera

that could achieve a best resolution of up to 1.4 m per pixel, the probe was

lost on 21 August 1993, three days before entering Martian orbit.

Predictably, the loss of the spacecraft prompted suggestions of conspiracy. They

can be discounted on the grounds of cost alone: had NASA wished to reassure the

public that it was interested in finding out more about the face whilst being

determined to prove it natural, it could have found a less expensive way of

doing it than sabotaging a mission designed to obtain better photographs.

Indeed, the less expensive means is what the conspiracy theorists suggested

about the results of the next probe, the Mars Global Surveyor: they declared the

first photograph of the ‘face’ obtained by the Mars Orbital Camera (frame

SPO-1-220/03) on 5 April 1998 to be fake. The original release of the photograph

in an unenhanced form ought to have reassured the public that NASA was being as

fair as possible.

Predictably, the loss of the spacecraft prompted suggestions of conspiracy. They

can be discounted on the grounds of cost alone: had NASA wished to reassure the

public that it was interested in finding out more about the face whilst being

determined to prove it natural, it could have found a less expensive way of

doing it than sabotaging a mission designed to obtain better photographs.

Indeed, the less expensive means is what the conspiracy theorists suggested

about the results of the next probe, the Mars Global Surveyor: they declared the

first photograph of the ‘face’ obtained by the Mars Orbital Camera (frame

SPO-1-220/03) on 5 April 1998 to be fake. The original release of the photograph

in an unenhanced form ought to have reassured the public that NASA was being as

fair as possible.

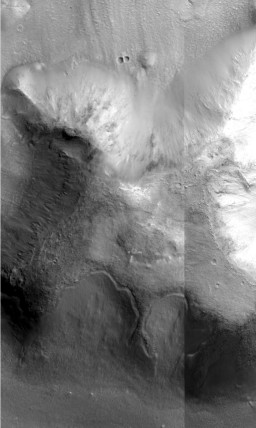

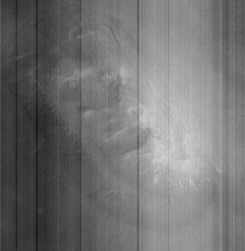

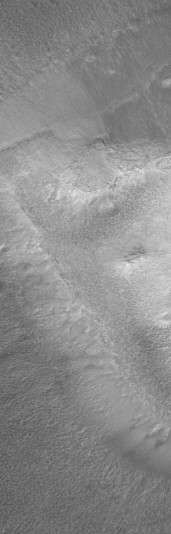

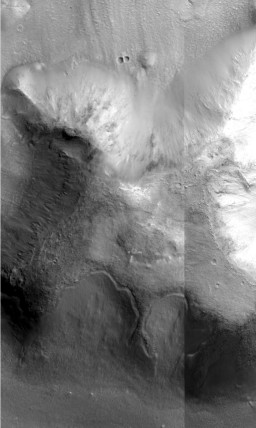

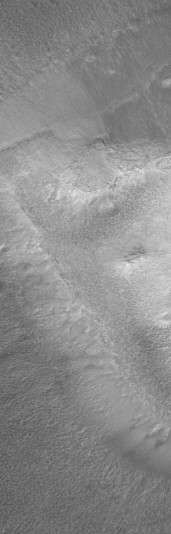

This prompted yet more

claims of unfair play when Malin Space Systems (which had designed the camera)

released an enhanced version on the following day, removing the more egregious

sampling errors from the raw data. The enhanced version shows none of the signs

of artificiality alleged for the 1970s images, despite the claims of its

supporters. The 1998 image, unlike the Viking Orbiter images, is an oblique,

with all the distortion that entails. Even

so, the ‘face’ appears as a highly eroded ridge, with a steep perimeter. A

second photograph from the Mars Orbital Camera, taken on 3 June 2000 and

released on 31 January 2001, shows only a small part of the ‘face’, but it

confirms the 1998 photograph in every respect. This one, by contrast, is a

near-vertical image. Supporters of artificiality have subsequently focused on

the bilateral symmetry of the object, with its central ridge (the nose) and the

apparent valley below the nose (the mouth); there is, however, no sign of a

depression to the northwest of the southwestern end of the ridge that would

provide the missing ‘left eye’, nor does the ridge appear to be central to

the mesa, confirming the lack of symmetry on the unprocessed version of Viking

Orbiter image 070A13. To explain the lack of resemblance to the original view of

the ‘face’ as a highly structured and artificial carving, they now have to

accept either that it has suffered a great deal of erosion from its pristine

form or that NASA has tampered with the photograph taken by the Mars Orbital

Camera, as it was the identification of the pristine form that led to the claims

for artificiality being made in the first place.

This prompted yet more

claims of unfair play when Malin Space Systems (which had designed the camera)

released an enhanced version on the following day, removing the more egregious

sampling errors from the raw data. The enhanced version shows none of the signs

of artificiality alleged for the 1970s images, despite the claims of its

supporters. The 1998 image, unlike the Viking Orbiter images, is an oblique,

with all the distortion that entails. Even

so, the ‘face’ appears as a highly eroded ridge, with a steep perimeter. A

second photograph from the Mars Orbital Camera, taken on 3 June 2000 and

released on 31 January 2001, shows only a small part of the ‘face’, but it

confirms the 1998 photograph in every respect. This one, by contrast, is a

near-vertical image. Supporters of artificiality have subsequently focused on

the bilateral symmetry of the object, with its central ridge (the nose) and the

apparent valley below the nose (the mouth); there is, however, no sign of a

depression to the northwest of the southwestern end of the ridge that would

provide the missing ‘left eye’, nor does the ridge appear to be central to

the mesa, confirming the lack of symmetry on the unprocessed version of Viking

Orbiter image 070A13. To explain the lack of resemblance to the original view of

the ‘face’ as a highly structured and artificial carving, they now have to

accept either that it has suffered a great deal of erosion from its pristine

form or that NASA has tampered with the photograph taken by the Mars Orbital

Camera, as it was the identification of the pristine form that led to the claims

for artificiality being made in the first place.

The face therefore emerges as an optical illusion (exactly as its discoverers in

1976 had claimed), known technically as pareidolia. This is the phenomenon that

allows believers to see an image of Mother Theresa in a cinnamon bun or the

Arabic name of Allah in a sliced aubergine. The basis of the illusion is the

human brain’s tendency to make understandable and detailed patterns from vague

stimuli; the same ability allows us to recognise melodies from short or

distorted fragments and to see numbers in patterns of dots used for tests of

colour blindness. Faces are one of the first patterns the infant human learns to

recognise, so it is unsurprising that a face-like mesa on Mars should be

‘read’ by so many as an actual representation of a human (or closely

humanoid) face.

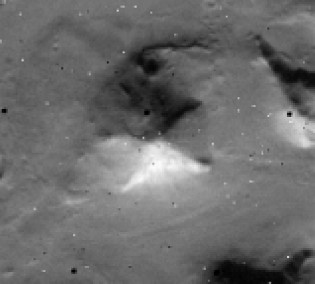

The ‘D&M Pyramid’

Close to the

‘face’, DiPietro and Molenaar noticed a number of angular peaks. Some of

these appeared to be geometrically regular and they dubbed them ‘pyramids’.

One in particular, to the southwest, appeared to possess impressive geometric

characteristics. It can be seen on image 035A72, to the right of the ‘face’

and a better view of it was obtained from image 070A13. From the shadow, it can

be calculated that the peak stands some 500 m above the surrounding plain.

Close to the

‘face’, DiPietro and Molenaar noticed a number of angular peaks. Some of

these appeared to be geometrically regular and they dubbed them ‘pyramids’.

One in particular, to the southwest, appeared to possess impressive geometric

characteristics. It can be seen on image 035A72, to the right of the ‘face’

and a better view of it was obtained from image 070A13. From the shadow, it can

be calculated that the peak stands some 500 m above the surrounding plain.

Richard Hoagland

dubbed it the D&M Pyramid, in honour of DiPietro and Molenaar, and the name

has stuck. The better photograph reveals it to be pentagonal with apparent

bilateral symmetry. The supposed main axis points towards the ‘face’; the

southwest angle points towards the ‘city’ and the northwest angle towards a

circular feature referred to as the ‘tholus’, named after its resemblance to

the Tholos tombs of the Aegean Early Bronze Age. A variety of mathematical

relationships have been claimed for the angles and the ratios between them,

involving the square roots of two and thee and the relationship e/π. These

relationships are impressive, but they depend on an assumption that one face of

the ‘pyramid’ has been damaged at some stage and that its shadowed face is

as apparently smooth as the undamaged faces.

When viewed on a

pixel-by-pixel basis, the ‘straight’ edges can be seen to diverge from their

supposed lines by up to two pixels (which, at the resolution of this photograph,

is equivalent to 86 m). Moreover, the sides that ought to be of identical length

for the ratios to be correct are not. The southwestern base measures 21.6 pixels

(calculated as the hypotenuse of a triangle whose two other sides are 12 and 18

pixels on the image), which calculates to be approximately 930 m; the

northwestern is 23.7 (i.e. √(112 + 212)) pixels or

1020 m. This is a difference of almost 10%. Similarly, the northern and southern

faces, which ought to be identical are 27.2 (√(82 + 262))

and 30.8 (√(72 + 302)) pixels respectively (or 1170

m and 1325 m), a difference of more than 13%. The calculations performed by Erol

Torun are based on Mark Carlotto’s enhancement of the image, which

interpolates data between pixels; the figures calculated here are based on the

original data, lengths of side being calculated by applying Pythagoras’s

Theorem to a direct count of pixels on Viking Orbiter frame 070A13. The margin

of error in each calculated length is not greater than one pixel, so even

allowing for this (and therefore accommodating Carlotto’s enhancements), we

cannot state that any two sides are of equal length. The data, poor as they are,

will simply not support the assertion. On this basis, we can discount the

geometric evidence supporting the contention that the ‘D&M Pyramid’ is

an artificial construction.

Moreover, the same Mars Orbital Camera frame that rephotographed the ‘face’

in 1998 also clipped the northwest corner of the ‘D&M Pyramid’ (at the

bottom left of the image reproduced here). This

confirms the analysis of the Viking Orbiter frames, that there is no convincing

evidence for artificiality whatsoever in the feature, even though only a small

part of it is covered by the image. The sides are not smooth in any sense, the

base does not consist of straight lines, nor is there a sharp angle at the

corner or between ‘faces’, at least on this part of the supposed monument.

In archaeological terms, the case can be considered closed.

Moreover, the same Mars Orbital Camera frame that rephotographed the ‘face’

in 1998 also clipped the northwest corner of the ‘D&M Pyramid’ (at the

bottom left of the image reproduced here). This

confirms the analysis of the Viking Orbiter frames, that there is no convincing

evidence for artificiality whatsoever in the feature, even though only a small

part of it is covered by the image. The sides are not smooth in any sense, the

base does not consist of straight lines, nor is there a sharp angle at the

corner or between ‘faces’, at least on this part of the supposed monument.

In archaeological terms, the case can be considered closed.

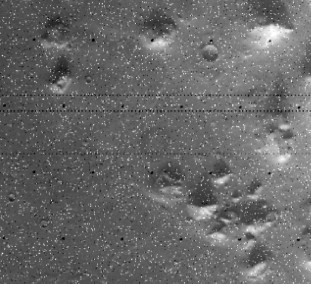

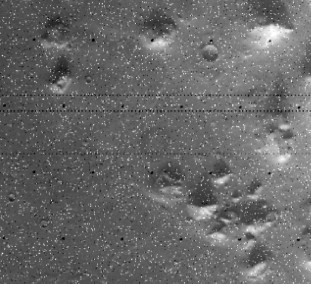

The ‘city’

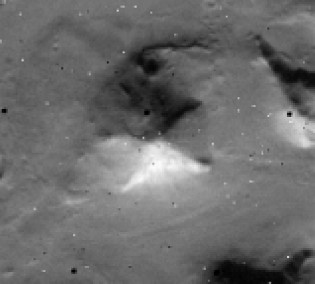

To the north of the face lies an area dubbed ‘the city’ because of its

supposed concentration of monuments. These principally consist of further

‘pyramids’, generally with three or five faces and therefore quite unlike

any human pyramids in Egypt or Mesoamerica. The same general problems that

attend the ‘D&M Pyramid’ apply here. The supposed regularity of these

structures vanishes once a careful count is made of pixel numbers on the raw

images and allowance is made for the margin of error in pixel size (which is 47

m on this photograph, 035A72). Moreover, the Mars Orbital Camera reveals a

mountain very similar to the D&M Pyramid. At the extreme northwestern end of

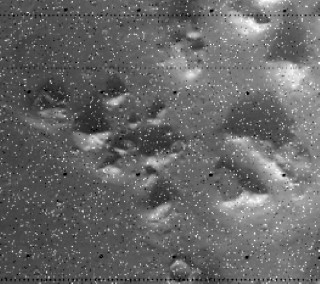

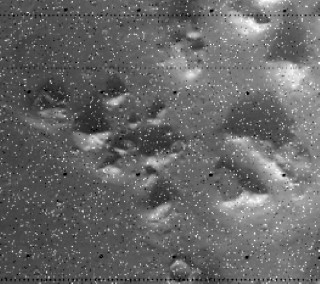

the monuments is the so-called ‘fort’, which, in DiPietro and Molenaar’s

enhancements, gains a row of cellular structures along its eastern edge. They

are too small to be visible on the original Viking Orbiter photograph, which

means that no amount of enhancement can bring them out: they can only be

artefacts of the enhancement process. The Mars Orbital Camera rephotographed the

‘fort’ on three separate occasions, each time appearing as a low hill with

erosion features that include apparently recent landslips.

To the north of the face lies an area dubbed ‘the city’ because of its

supposed concentration of monuments. These principally consist of further

‘pyramids’, generally with three or five faces and therefore quite unlike

any human pyramids in Egypt or Mesoamerica. The same general problems that

attend the ‘D&M Pyramid’ apply here. The supposed regularity of these

structures vanishes once a careful count is made of pixel numbers on the raw

images and allowance is made for the margin of error in pixel size (which is 47

m on this photograph, 035A72). Moreover, the Mars Orbital Camera reveals a

mountain very similar to the D&M Pyramid. At the extreme northwestern end of

the monuments is the so-called ‘fort’, which, in DiPietro and Molenaar’s

enhancements, gains a row of cellular structures along its eastern edge. They

are too small to be visible on the original Viking Orbiter photograph, which

means that no amount of enhancement can bring them out: they can only be

artefacts of the enhancement process. The Mars Orbital Camera rephotographed the

‘fort’ on three separate occasions, each time appearing as a low hill with

erosion features that include apparently recent landslips.

One of the ‘pyramids’ in the

‘city square’ in a Mars Global Surveyor image

The ‘fort’ as seen by the Viking

Orbiter and the Mars Global Surveyor

[i] The text of the press

release runs: Viking 1-61 P-17384 (35A72) July 31, 1976 This picture is

one of many taken in the northern latitudes of Mars by the Viking 1 Orbiter

in search of a landing site for Viking 2. The picture shows eroded mesa-like

landforms. The huge rock formation in the centre, which resembles a human

head, is formed by shadows giving the illusion of eyes, nose and mouth. The

feature is 1.5 kilometres (one mile) across, with the sun angle at

approximately 20 degrees. The speckled appearance of the image is due to bit

errors, emphasized by enlargement of the photo. The picture was taken on

July 25 from a range of 1873 kilometres (1162 miles). Viking 2 will arrive

in Mars orbit next Saturday (August 7) with a landing scheduled for early

September.

The ‘face’ has

been known as that since NASA engineers dubbed it such as a convenient shorthand

[i].

Located at about 40.9ºN 9.45ºW, it was photographed by the Viking Orbiters 1

on 25 July 1976 whilst obtaining images of a site suitable for Viking Lander 2.

Eighteen images of the region were taken, but of these, eleven have resolutions

worse than 550 m per pixel (in other words, no feature less than 550 m across

can be seen on these images). Only two of them (frames 070A13, taken on 24

August 1976, and 035A72, taken on 20 July 1976) have resolutions of better than

50 m per pixel. They show a subrectangular elevated feature that displays

roughly bilateral symmetry similar to a human face. The length is estimated as 2

km, the width as 1.5 km and the height as about 400 m. The long axis of the face

is aligned at a bearing of approximately 329º to the Martian North Pole. In

Image 070A13, the sun is 28º above the horizon, while in 035A72, it is 11º;

these differences in angle reveal slightly different details in the ‘face’.

The ‘face’ has

been known as that since NASA engineers dubbed it such as a convenient shorthand

[i].

Located at about 40.9ºN 9.45ºW, it was photographed by the Viking Orbiters 1

on 25 July 1976 whilst obtaining images of a site suitable for Viking Lander 2.

Eighteen images of the region were taken, but of these, eleven have resolutions

worse than 550 m per pixel (in other words, no feature less than 550 m across

can be seen on these images). Only two of them (frames 070A13, taken on 24

August 1976, and 035A72, taken on 20 July 1976) have resolutions of better than

50 m per pixel. They show a subrectangular elevated feature that displays

roughly bilateral symmetry similar to a human face. The length is estimated as 2

km, the width as 1.5 km and the height as about 400 m. The long axis of the face

is aligned at a bearing of approximately 329º to the Martian North Pole. In

Image 070A13, the sun is 28º above the horizon, while in 035A72, it is 11º;

these differences in angle reveal slightly different details in the ‘face’. The ‘face’ lies

close to the boundary between an area of flat-topped mesas and conical hills to

its southwest, and a much flatter region in which it lies. Claims have been made

for the presence of a former shoreline close to the ‘face’, which may be

important in considering its likely origin. Erosion is generally cited as the

main factor in the creation of the landforms in this region, but a variety of

claims were made during the 1980s and 90s that this was not sufficient to

explain a number of features of the ‘face’. The original view of astronomers

was that the northern past of Mars had originally been covered with a sediment

that subsequently eroded, perhaps as a result of wind action. As evidence for

the former presence of surface water on the planet has increased, so it has

begun to seem more likely that the erosion in this region may have been

exacerbated by former seas.

The ‘face’ lies

close to the boundary between an area of flat-topped mesas and conical hills to

its southwest, and a much flatter region in which it lies. Claims have been made

for the presence of a former shoreline close to the ‘face’, which may be

important in considering its likely origin. Erosion is generally cited as the

main factor in the creation of the landforms in this region, but a variety of

claims were made during the 1980s and 90s that this was not sufficient to

explain a number of features of the ‘face’. The original view of astronomers

was that the northern past of Mars had originally been covered with a sediment

that subsequently eroded, perhaps as a result of wind action. As evidence for

the former presence of surface water on the planet has increased, so it has

begun to seem more likely that the erosion in this region may have been

exacerbated by former seas. The initial announcement of the discovery of this feature dismissed it as being

‘formed by shadows giving the illusion of eyes, nose and mouth’. The public

took little notice of it until DiPietro and Molenaar published an analysis of

the formation in 1982, in which they concluded that it was artificial. Since

then, a number of popular writers have taken up the theme, most notably Richard

Hoagland and Graham Hancock. The widespread availability of computers for

processing digital images from the mid-1980s onwards led to a great deal of

amateur work on the Viking Orbiter photographs. Different techniques for

enhancing the photographs have been used, including techniques that attempt to

deduce three-dimensional shape from shadows, the interpolation of pixels and so

on. These techniques were all used to make the ‘face’ appear more detailed

and more humanoid than on the original satellite images. The ‘face’ has

become an iconic image, familiar to millions; its ghost-like features stare

blankly from the covers of numerous books and videos. Demands for photographs of

higher quality than those of 1976—with their resolutions of no better than 43

m per pixel—grew during the 1990s, especially when NASA announced the

forthcoming launch of Mars Observer on 22 September 1992. Equipped with a camera

that could achieve a best resolution of up to 1.4 m per pixel, the probe was

lost on 21 August 1993, three days before entering Martian orbit.

The initial announcement of the discovery of this feature dismissed it as being

‘formed by shadows giving the illusion of eyes, nose and mouth’. The public

took little notice of it until DiPietro and Molenaar published an analysis of

the formation in 1982, in which they concluded that it was artificial. Since

then, a number of popular writers have taken up the theme, most notably Richard

Hoagland and Graham Hancock. The widespread availability of computers for

processing digital images from the mid-1980s onwards led to a great deal of

amateur work on the Viking Orbiter photographs. Different techniques for

enhancing the photographs have been used, including techniques that attempt to

deduce three-dimensional shape from shadows, the interpolation of pixels and so

on. These techniques were all used to make the ‘face’ appear more detailed

and more humanoid than on the original satellite images. The ‘face’ has

become an iconic image, familiar to millions; its ghost-like features stare

blankly from the covers of numerous books and videos. Demands for photographs of

higher quality than those of 1976—with their resolutions of no better than 43

m per pixel—grew during the 1990s, especially when NASA announced the

forthcoming launch of Mars Observer on 22 September 1992. Equipped with a camera

that could achieve a best resolution of up to 1.4 m per pixel, the probe was

lost on 21 August 1993, three days before entering Martian orbit. Predictably, the loss of the spacecraft prompted suggestions of conspiracy. They

can be discounted on the grounds of cost alone: had NASA wished to reassure the

public that it was interested in finding out more about the face whilst being

determined to prove it natural, it could have found a less expensive way of

doing it than sabotaging a mission designed to obtain better photographs.

Indeed, the less expensive means is what the conspiracy theorists suggested

about the results of the next probe, the Mars Global Surveyor: they declared the

first photograph of the ‘face’ obtained by the Mars Orbital Camera (frame

SPO-1-220/03) on 5 April 1998 to be fake. The original release of the photograph

in an unenhanced form ought to have reassured the public that NASA was being as

fair as possible.

Predictably, the loss of the spacecraft prompted suggestions of conspiracy. They

can be discounted on the grounds of cost alone: had NASA wished to reassure the

public that it was interested in finding out more about the face whilst being

determined to prove it natural, it could have found a less expensive way of

doing it than sabotaging a mission designed to obtain better photographs.

Indeed, the less expensive means is what the conspiracy theorists suggested

about the results of the next probe, the Mars Global Surveyor: they declared the

first photograph of the ‘face’ obtained by the Mars Orbital Camera (frame

SPO-1-220/03) on 5 April 1998 to be fake. The original release of the photograph

in an unenhanced form ought to have reassured the public that NASA was being as

fair as possible. This prompted yet more

claims of unfair play when Malin Space Systems (which had designed the camera)

released an enhanced version on the following day, removing the more egregious

sampling errors from the raw data. The enhanced version shows none of the signs

of artificiality alleged for the 1970s images, despite the claims of its

supporters. The 1998 image, unlike the Viking Orbiter images, is an oblique,

with all the distortion that entails.

This prompted yet more

claims of unfair play when Malin Space Systems (which had designed the camera)

released an enhanced version on the following day, removing the more egregious

sampling errors from the raw data. The enhanced version shows none of the signs

of artificiality alleged for the 1970s images, despite the claims of its

supporters. The 1998 image, unlike the Viking Orbiter images, is an oblique,

with all the distortion that entails. Close to the

‘face’, DiPietro and Molenaar noticed a number of angular peaks. Some of

these appeared to be geometrically regular and they dubbed them ‘pyramids’.

One in particular, to the southwest, appeared to possess impressive geometric

characteristics. It can be seen on image 035A72, to the right of the ‘face’

and a better view of it was obtained from image 070A13. From the shadow, it can

be calculated that the peak stands some 500 m above the surrounding plain.

Close to the

‘face’, DiPietro and Molenaar noticed a number of angular peaks. Some of

these appeared to be geometrically regular and they dubbed them ‘pyramids’.

One in particular, to the southwest, appeared to possess impressive geometric

characteristics. It can be seen on image 035A72, to the right of the ‘face’

and a better view of it was obtained from image 070A13. From the shadow, it can

be calculated that the peak stands some 500 m above the surrounding plain. Moreover, the same Mars Orbital Camera frame that rephotographed the ‘face’

in 1998 also clipped the northwest corner of the ‘D&M Pyramid’ (at the

bottom left of the image reproduced here). This

confirms the analysis of the Viking Orbiter frames, that there is no convincing

evidence for artificiality whatsoever in the feature, even though only a small

part of it is covered by the image. The sides are not smooth in any sense, the

base does not consist of straight lines, nor is there a sharp angle at the

corner or between ‘faces’, at least on this part of the supposed monument.

In archaeological terms, the case can be considered closed.

Moreover, the same Mars Orbital Camera frame that rephotographed the ‘face’

in 1998 also clipped the northwest corner of the ‘D&M Pyramid’ (at the

bottom left of the image reproduced here). This

confirms the analysis of the Viking Orbiter frames, that there is no convincing

evidence for artificiality whatsoever in the feature, even though only a small

part of it is covered by the image. The sides are not smooth in any sense, the

base does not consist of straight lines, nor is there a sharp angle at the

corner or between ‘faces’, at least on this part of the supposed monument.

In archaeological terms, the case can be considered closed. To the north of the face lies an area dubbed ‘the city’ because of its

supposed concentration of monuments. These principally consist of further

‘pyramids’, generally with three or five faces and therefore quite unlike

any human pyramids in Egypt or Mesoamerica. The same general problems that

attend the ‘D&M Pyramid’ apply here. The supposed regularity of these

structures vanishes once a careful count is made of pixel numbers on the raw

images and allowance is made for the margin of error in pixel size (which is 47

m on this photograph, 035A72). Moreover, the Mars Orbital Camera reveals a

mountain very similar to the D&M Pyramid. At the extreme northwestern end of

the monuments is the so-called ‘fort’, which, in DiPietro and Molenaar’s

enhancements, gains a row of cellular structures along its eastern edge. They

are too small to be visible on the original Viking Orbiter photograph, which

means that no amount of enhancement can bring them out: they can only be

artefacts of the enhancement process. The Mars Orbital Camera rephotographed the

‘fort’ on three separate occasions, each time appearing as a low hill with

erosion features that include apparently recent landslips.

To the north of the face lies an area dubbed ‘the city’ because of its

supposed concentration of monuments. These principally consist of further

‘pyramids’, generally with three or five faces and therefore quite unlike

any human pyramids in Egypt or Mesoamerica. The same general problems that

attend the ‘D&M Pyramid’ apply here. The supposed regularity of these

structures vanishes once a careful count is made of pixel numbers on the raw

images and allowance is made for the margin of error in pixel size (which is 47

m on this photograph, 035A72). Moreover, the Mars Orbital Camera reveals a

mountain very similar to the D&M Pyramid. At the extreme northwestern end of

the monuments is the so-called ‘fort’, which, in DiPietro and Molenaar’s

enhancements, gains a row of cellular structures along its eastern edge. They

are too small to be visible on the original Viking Orbiter photograph, which

means that no amount of enhancement can bring them out: they can only be

artefacts of the enhancement process. The Mars Orbital Camera rephotographed the

‘fort’ on three separate occasions, each time appearing as a low hill with

erosion features that include apparently recent landslips.